I’ll shove your gamepad down your throat: the history of violence in video games

The violence in video games has been a scapegoat since day one: mass media uses it to scare housewives and old people, it gets censored and banned and everyone is hellbent on finding that link between violence in games and anger issues in teens. Sometimes debates get heated up beyond any reason. It’s time to leave all the scandals and investigations to so-called experts and take a good look on violence as an artistic device. From that point of view God of War developers are truly the masters of that art. So, let’s celebrate Kratos’s comeback – he may be old and beaten up but still strong as a horse – and find out how violence have been affecting video games and vice versa.

A bunch of evil pixels

Things were easier at the dawn of gaming industry, when Atari 2600 has been the pinnacle of gaming console design and arcades were at the peak of their popularity. Nobody really minded age restrictions back then. This doesn’t mean that all the entertainment was cut out entirely for children. It just so happened that in the 70’s cinema was drenched in blood: grindhouse got quite popular, some movie theaters got off with showing pornography, and Martin Scorsese was releasing his best violent movies like Taxi Driver. Videogames were clearly losing that battle – a bunch of pixels could not compete with spectacular cinematic gore.

Death Race – who would really believe that virtual violence of 70’s looked like this?

Still, game developers were trying hard to impress their audience. Though they didn’t try hard to develop a plot: they just took the events of popular movies, tied them in with the gameplay and let the gamers’ imagination run free in the land of pixelated graphics. James Rolfe, a.k.a. AVGN, describes this game design in a pretty sarcastic tone: «You wanna know a recipe for shit? Take a movie, put it on NES, n' you got yourself some shit». That’s exactly how Death Race came to be – it was inspired by post-apocalyptic action movie Death Race 2000. It was the first game in history of videogames where plot revolved solely around killing things. It was released on arcade machines in 1976, and the whole gameplay consisted of driving a car and running people over. One round was 25 cents. If you want to play with your friend – 50 cents. Reminds of Carmageddon in a way, doesn’t it?

It’s hard to imagine now that game with monochrome pixel graphics would be branded as «murder simulator» by mass media. But public outcry was much louder back then, so Exidy employees responsible for creation of Death Race had to publicly explain that you have to kill gremlins in the game, not people. Developers decided to ride the hype wave and started working on a sequel called Chase.

Gamers were already getting the taste of virtual violence, and sooner or later Atari was bound to get on that bandwagon. There was one problem though – the head of Atari, Nolan Bushnell, was strictly against violence in videogames. His stance was quite reasonable – the target audience of Atari were parents who bought consoles so their children would stay home instead of wasting money at arcades. That might explain the fact the The Texas Chainsaw Massacre that was based on the cult slasher movie came out in 1983, when Atari was going downhill with the whole industry. Also, in this game it’s quite clear that playable character is a serial killer murdering people and not gremlins or robots.

Game console developers held family values above all else back in the 80-s. Japanese company Nintendo replaced Atari as the leader of home entertainment and followed the same family-friendly path. But still waters run deep. Take Chiller, for example, that was heavily cut down and released on NES. It was filled to the brim with gore and torture scenes. Still, this was probably just an exception and game probably never made it’s way into children’s Christmas gifts.

It’s a whole different story when it comes to PC games. In Death Wish 3 (1986) for Commodore 64 main character was busy beating grannies to death and exploding people with a bazooka, Jack the Ripper had shocking loading screens and Barbarian: The Ultimate Warrior gave gamers a chance to cut off their enemy’s head and see it roll on the arena. This last one had really eye-catching advertisements – it had scantily clad girls, big buff athletes and all the other stuff you usually see on a Manowar album cover. Moral crusaders were up in arms against that game – it even got banned in Germany – but, as with Death Race, the scandal just boosted the sales.

SEGA hits right off the bat

There was only one company that could end all this violence-shy nonsense and it’s name was SEGA. They had to compete with Nintendo, which wasn’t an easy task. They worked hard and kept the idea of arcade machines in mind while developing Mega Drive. The good old violence was a solid stepping stone for one of the best gaming platforms and an extra aggressive promotional campaign. Slogan «Genesis does what Nintedon’t» was all over the place and we all heard the term «blast processing» without even having a clue what it really means. The advertisement still worked though – everybody praised SEGA for being the coolest game developers.

There is no arguing that this gaming console had some undeniable advantage in comparison to others. This advantage came in form of awesome exclusive games that allowed players to shoot people, explode stuff, fight a lot and kick asses in general. The SEGA managers were operating on the premise that if Nintendo treats it’s audience like babies and steps on it’s own throat by cutting out blood from Super Castlevania IV, then SEGA must do exactly the opposite.

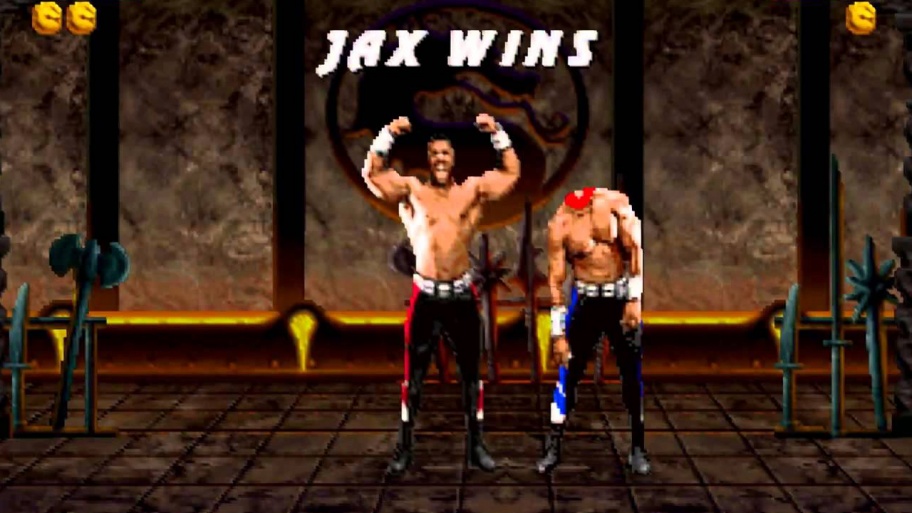

It took Mortal Kombat to realize that all the fighting games before it were practically toothless and bloodless.

Of course, SEGA also released a beautiful child-friendly platformer The Lion King, not to mention various Sonic the Hedgehog games which certainly didn’t make anyone’s blood boil. Still, it was the same company that released Mortal Kombat games that still hold record in violent finishing combos. Many boys still hold dear those memories of watching the pixel fighters shredding their enemies and spilling their blood. Violence combined with images of real actors in sprites made the gameplay scarily realistic – apart from robots, colorful ninjas and fantasy setting, of course. No wonder this fighting game triggered a chain reaction – even the most progressive gamers realized that there is a need for an age restriction system.

MK wasn’t the only one to get noticed by US Senate Committee. Another game that got censored was Night Trap – and it’s quite ridiculous, actually, as the whole game was comprised of video clips and wasn’t that violent to begin with. The Committee still found the lack of age restriction appalling. Look at these maniacs with knives! Look at all these topless women! Their cries were loud enough to force all the game developers to agree to censorship. Thus, the infamous ESRB (Electronic Software Rating Board) was born. The developers realized that you can make anything you want if you stick the right label on the box.

Technologies that make you suffer

Violence became an engine for technical progress since the release of cult classic Doom in 1993. Shooters have their own rules – weapons have to shoot and cut effectively so player would enjoy killing enemies, be they Martian demons, zombies or even religious fanatics. To reach that goal game had to be visually striking and work well, which means it had to have a modern engine. You could forgive RPGs, strategy games or platformers like Mario for simplistic graphics, but it’s not the case with shooters. When developers could not produce top-notch imagery, they were compensating it with various gaming possibilities. A good example of this is Blood where players could tear off the heads of their enemies and just kick them around.

Doom was the first shooter that got blamed for contributing to aggression in teenagers.

Even with such bloody progress the topic of killing people was still pretty dangerous. It was the case with previously mentioned Death Race, where you could kill gremlins but not pixel people – even though they look exactly the same. The idea of that game was repurposed 20 years later in a racing game Carmageddon that allowed to run over pedestrians freely. Obviously, the game got censored in some countries: in Germany the human characters were replaced with robots, in England and Italy – with zombies. All the excuses like “but that’s how I see it” weren’t helping either: the developer of Harvester was trying to explain the link between virtual violence and reality through gameplay, but ultimately failed. The game had some nasty scenes, like the one where children eat their mother’s corpse, so public disapproval and commercial failure were inevitable.

However, shooter developers found a brilliant solution: if all the enemies are bad guys — terrorists, serial killers, thugs or nazis — there’s no shame in killing them. Nowadays we can shoot human characters without feeling any guilt — thanks to Medal of Honor, the first game to use this idea. This game had set the record straight and made it clear: you can kill Wehrmacht soldiers but not your comrades. Come on, everybody knows nazis are the evil incarnate. This stuff didn’t matter that much in games like Wolfenstein 3D but with development of 3D graphics this rule got imperative for the whole genre. If you want to let player get away with murder, you have to make the victims dirty rotten bastards.

Let’s take a look at Half-life to understand the idea. Our favorite silent protagonist Gordon Freeman has to kill monsters before moving onto killing humans – special forces troops sent to wipe out the whole Black Mesa. Do you remember how they were introduced? As the troops arrived they started to kill scientists, even though they could remove all the guards first and even kill the main character. It becomes obvious that these guys are operating under some evil authority so they are practically nazis. Oh, by the way, have you ever played Soldier of Fortune that came out back in 2000? Yeah, that one where you can shoot off heads, arms, legs, etc. Game engine supported about 26 pressure points allowing player to torment their victim in various ways before finally killing it. Of course, you can’t hurt innocent bystanders like that, but if they are terrorists threatening the world with an atomic bomb – sure, go ahead, have fun. Still better than running over pedestrians, though.

Teenagers were discussing Soldier of Fortune killings with a bated breath like it was some sort of horrifying secret.

Just finish me already

Killings are only one part of heart and soul of violence in videogames. Another gruesome part of it is body horror. The main difference here is that various character are being violated upon not by a hero but by a third party – aliens, viruses, gene mutations, demons or other evil beings. All these forces alter everymen into dreadful monsters in horrifying painful ways.

The main character here has to act like an angel of mercy, bringing the suffering of those poor creatures to the end. There are many methods player can employ to get it done – beating, dismemberment, a cleansing fire. None of it really matters in the context of humanistic nature of the executioner (the player himself), because in the end it’s the beauty of order that prevails over the mutated abhorrence. There’s no way you could pull this trick off with human characters: would you really gut them out with a chainsaw or pull out their spine through their ass just because they’ve done something wrong?

Golden age of body horror in movies happened way before videogames began to explore this theme – take, for instance, John Carpenter’s Thing or David Cronenberg’s The Fly. This creative device was so successful that game developers just couldn’t pass the opportunity to explore it. That’s how Resident Evil (1996) with the Umbrella corporation and it’s virus came to be. It’s not the single example of body horror done right – take a look at Parasite Eve (1998), where laws of genetics prevail over common sense, or Silent Hill (1999) with it’s creatively designed charming monstrosities. All these games are full of violence and body horror but none of them demand the players to break the common rules of morality. They are filled to the brim with horror and gore and censors can’t even complain about it.

In the age of easy virtual killing only remastered classics remind us how hard and confusing gameplay was back then.

It’s hard to cross the line in body horror, and it’s evident by Japanese horror movies and also by a survival horror classic Dead Space (2008). It managed to collect every body horror cliché possible, starting from Necromorph designs clearly inspired by car crash victims, various way of mutilation and an ability to burn enemies with a flamethrower. The creepy thing is that some scenes show us the origins of the monsters – they used to be women, children, Ishimura station workers and main character’s colleagues. As soon as they stop being humans, you are allowed to destroy them however you please.

The art of violence

We are already used to the idea of videogames as a type of art. If we gonna keep believing that, it’s better to accept that the most progressive, creative and exciting games are connected with violence in one way or another. Amongst the best games of all time rated by Metacritic are shooters like Half-Life 2 and GTA 4 and 5 – not that bloody and aggressive, but still filled with violence. It’s pretty obvious that shooters of all kinds allow us to blow off some steam, get some new raw emotions and enjoy our virtual victories. Still, there is a question that needs to be answered – where is the line that divides mindless killings in games and violence as an artistic device?

It’s also important to find the answer in the wake of violence for the sake of violence. The first example here is Manhunt that was released back in 2003, where players had to brutally destroy the enemies just because the game says so – they weren’t nazis or zombies but human characters trying to survive in a snuff reality show. Another game that comes to mind is Postal 2 released by Running with Scissors in the same year. Developers claimed that it’s impossible to progress in the game unless you use a cat as a silencer and chop off heads with a shovel, but if you take the violence out the gameplay turns out to be quite boring. These games always get banned and scolded – and fairly so – but all the hate just attracts more and more gamers. Postal Dude has left quite a legacy – otherwise why would there be such weird creations as Hatred? It’s obvious that you can’t just add aesthetics to this trash and call it an art.

That’s what must have attracted people to play Postal 2.

If developers did not add any meaning into the bloodbath, if the violence in their game isn’t connected to unique gameplay that underlines the creativity in that violence, than the game is more likely to fail. You don’t play Postal 2 for gameplay, plot or beautiful scenery. Just to make things clear and find that line between blatant showoff and real creativity try to remember all the emotions rushing in when you watched Ethan from Heavy Rain sawing his finger off or the dreadful eye surgery scene with Isaac Clarke in Dead Space 2. Try to remember how you pushed the sticks on your Dualshock gamepad so Kratos would blind his enemy in God of War III – the camera angle here was just as important as this physical involvement in character’s action. All these moments are memorable and intriguing, they are the reason we compare game developers to artists. As long as violence is used creatively in the games, we can discuss it freely without having to watch out for harsh critics to strike.

source: link

Comments